The Disenfranchisement of Paniyas in Kerala

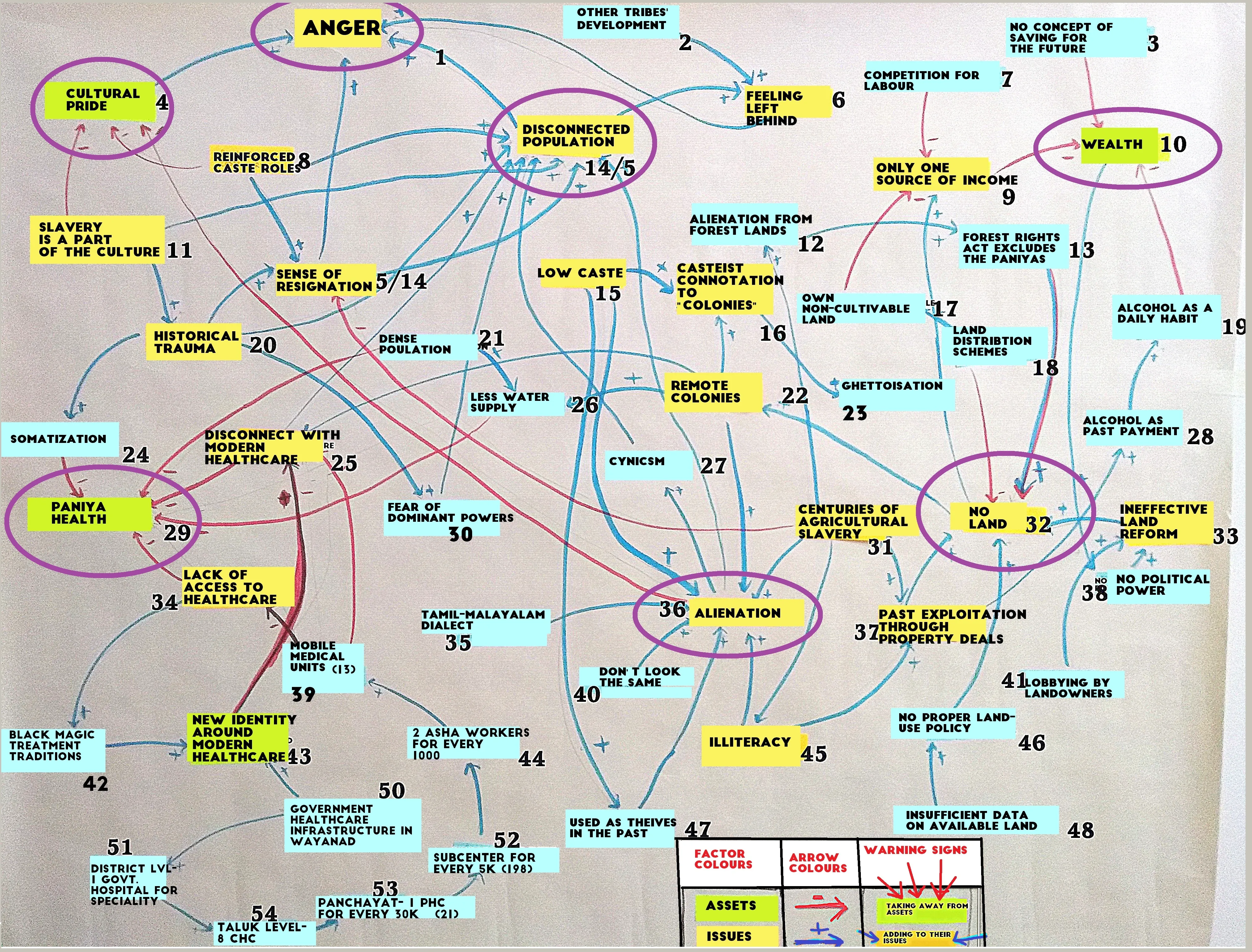

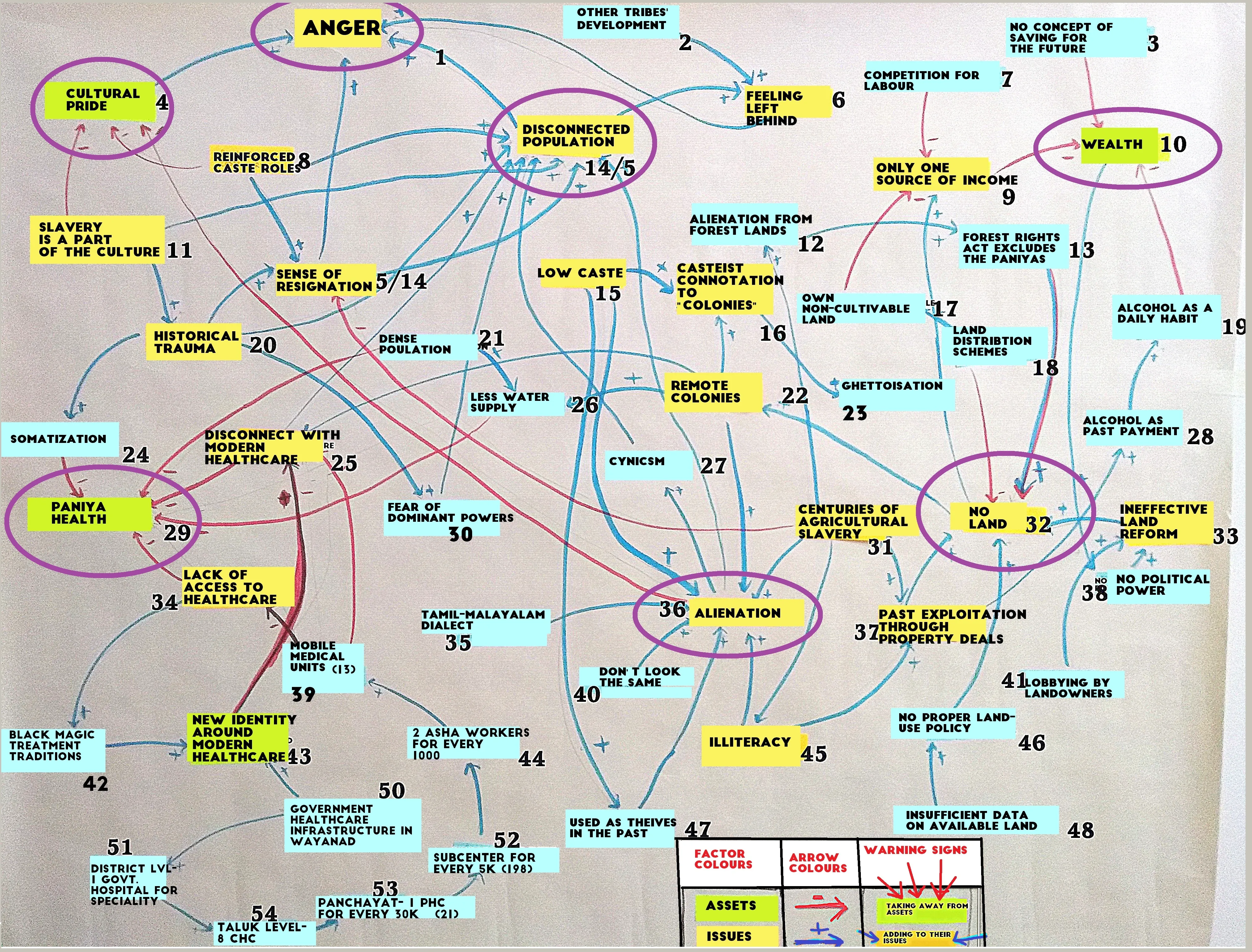

By studying the literature around the Paniya tribe, I cover topics such as population, caste names and structures in Wayanad, periods of Paniya history, …

Research rooted in specific places and accountable to the people it concerns- from Bidar and Wayanad to rural Bihar and Bangalore.

The work collected here begins in specific places and stays close to the ground. It is research that does not abstract away from where it happens- the places shape the methods, the people shape the questions, and the findings belong first to the communities that made them possible.

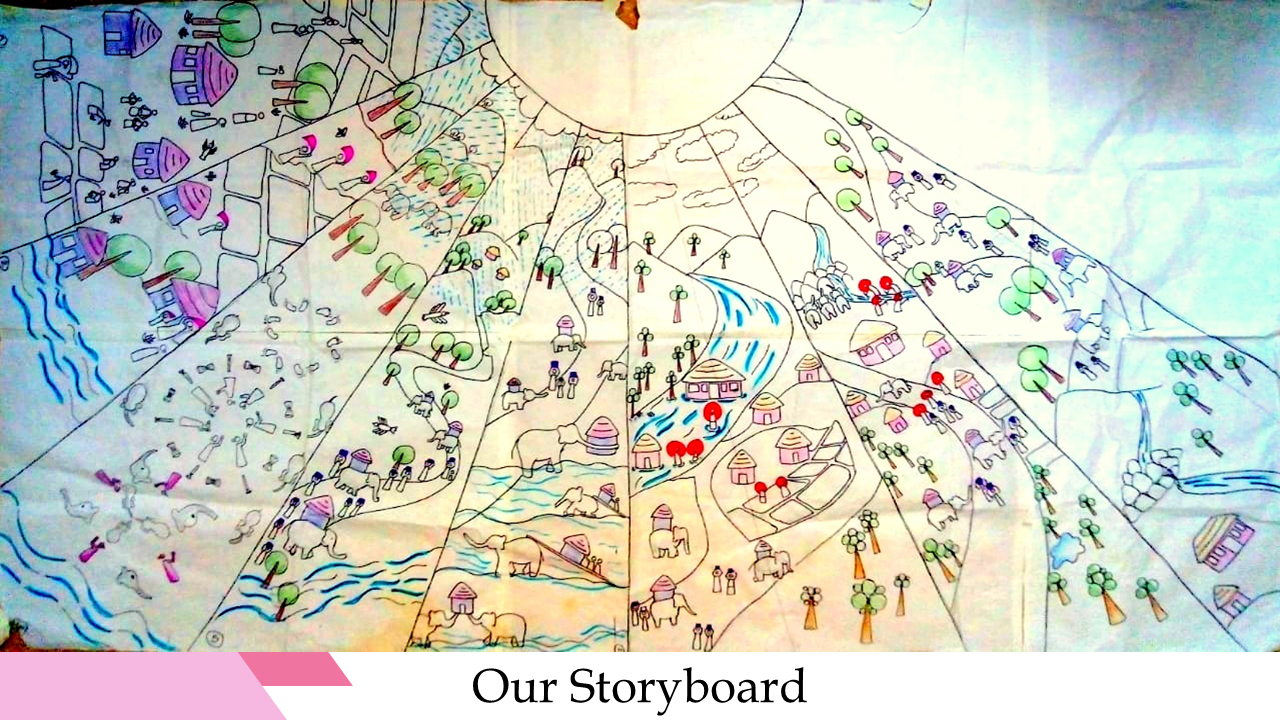

In Bidar, the mesh network experiments were inseparable from the social fabric of the communities hosting them. The women whose oral knowledge practices the network was meant to serve were not “users” of a technology but collaborators in imagining what connectivity could mean when it is not mediated by commercial ISPs. In Wayanad, a literature review on the systemic disenfranchisement of the Paniya community- centuries of enslavement, landlessness, exclusion from education- became the ground for a speculative storytelling tool that asked Adivasi children to imagine futures for themselves through tapestry-making, using elephants from their own Vattakalli dance tradition as symbols of self-belief.

In rural Bihar, participatory mapping with communities in Kishanganj revealed how caste-based power structures shape everything from school placement to village infrastructure to the aspirations parents hold for their children. In Koramangala, the method was attentiveness itself- watching the buffaloes that pass through at dawn, the sanitation workers, the garbage trucks, the hidden rhythms of a neighbourhood most people only see as a tech hub.

Mapping migratory routes of pastoralist communities across India combined GIS with indigenous knowledge, making visible land-use patterns that urbanisation and policy changes are disrupting. The climate resource centre in Bidar surfaced agrarian heuristics- seasonal knowledge, care practices, mythic narratives- that farming communities use to read and respond to ecological change.

What connects these projects is not a discipline but a commitment: research should be accountable to the places and people it engages with. The methods change with every place, because the place demands it.

By studying the literature around the Paniya tribe, I cover topics such as population, caste names and structures in Wayanad, periods of Paniya history, …

A transdisciplinary research project in collaboration with Project Potential Trust, Kishanganj, delving into the impact of the caste system on education and …

I explore the intricate relationship between care, collaboration, and networks within various collectives, delving into my experiences in Team YUVAA, Living …

A poetic reflection on the hidden rhythms and overlooked details of daily life in Koramangala, Bangalore.

Interviewed farmers, seed distributors, agrarian scientists, and published pieces about local agrarian practices, mythic narratives and heuristics used by …

Documentation of a project to collect, visualize, and integrate data about seasonal migratory routes of pastoralist communities across India.

The output of a 5-week course in Wayanad, Kerala, in the aftermath of the 2018 floods. We designed a speculative storytelling tool that asks how communities can …

This piece is a group reflection of a project run in Bidar, India, to set up a community mesh network facilitated by Living Labs Network and Forum, Team YUVAA …