Milli - Connect and Annotate your Archives

Milli was an open-source platform designed to make archives more democratic in the described and annotated ways. The core was to achieve this using the W3C Web …

Who holds memory, how should archives work, and what does annotation enable? From institutional platforms to community audio archives.

This thread follows a concern with who gets to hold memory and how. Archives are not neutral containers- they reflect decisions about what is worth preserving, in whose language, and on whose terms.

The work begins with Milli, an open-source platform designed to let communities annotate institutional archives rather than merely consume them. The W3C Web Annotation Standard became central- a way to layer multiple interpretations onto the same record, so that a photograph in a museum collection could carry the reading of a scholar and the memory of a community elder. Presenting Milli at International Archives Week surfaced the tension between institutional archival practices and the communities those archives claim to represent.

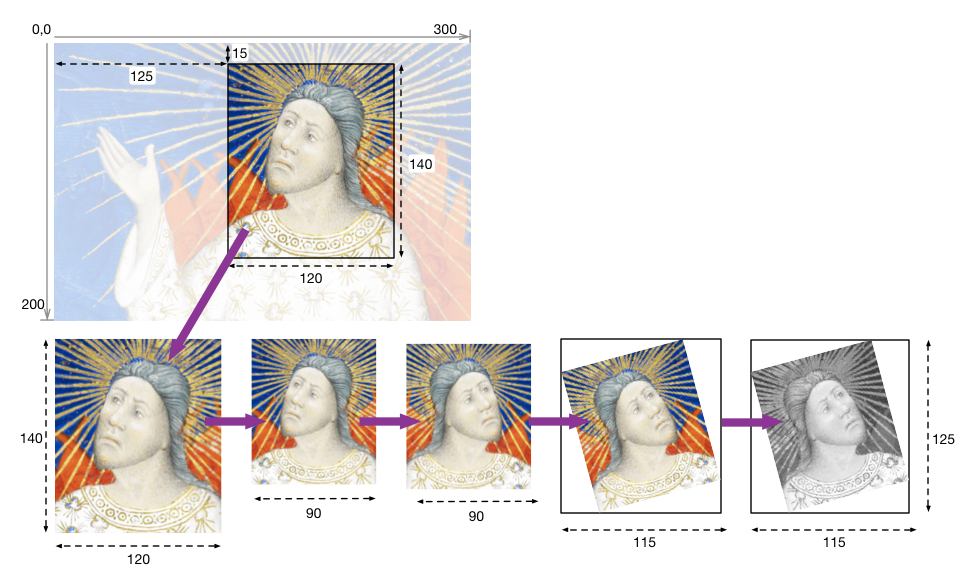

Behind these interfaces lies a question of infrastructure. IIIF offered a path for small archives to host and share images without the weight of enterprise systems- a search that took years and multiple false starts before workable low-code solutions emerged. The broader landscape of South Asian digital history revealed how unevenly the region’s cultural and technological past has been digitised, and for whom.

The Wikipedia editathon during Dalit History Month was a different kind of archival intervention- working within the platform that shapes how millions encounter history, addressing the systematic absence of Dalit literary and intellectual traditions from the encyclopaedia. Knowledge gaps on Wikipedia are not accidents; they are traces of whose histories have been considered worth documenting.

Papad closes the loop by returning to community-held knowledge. Where Milli handles metadata and text, and IIIF handles images, Papad works with audio- the medium closest to how oral communities already share what they know. Deployed over decentralised mesh networks in Karnataka villages, it asks what an archive looks like when it lives inside the community it belongs to rather than in an institution that studies it.

Milli was an open-source platform designed to make archives more democratic in the described and annotated ways. The core was to achieve this using the W3C Web …

Contributed a total of 24.5K words across 27 edited articles, including the creation of 2 new articles. Added 167 references, made 2 Commons uploads, and …

Presented the designs for the Milli platform at International Archives Week, demonstrating its capabilities for collaborative discovery, annotation, and …

Papad is a tool for community-based practitioners to store and access oral knowledge bases, deployed over decentralised community networks in Karnataka villages …

A curated collection of web content exploring the history of the digital in South Asia and the digitization of South Asian cultural and historical artifacts.

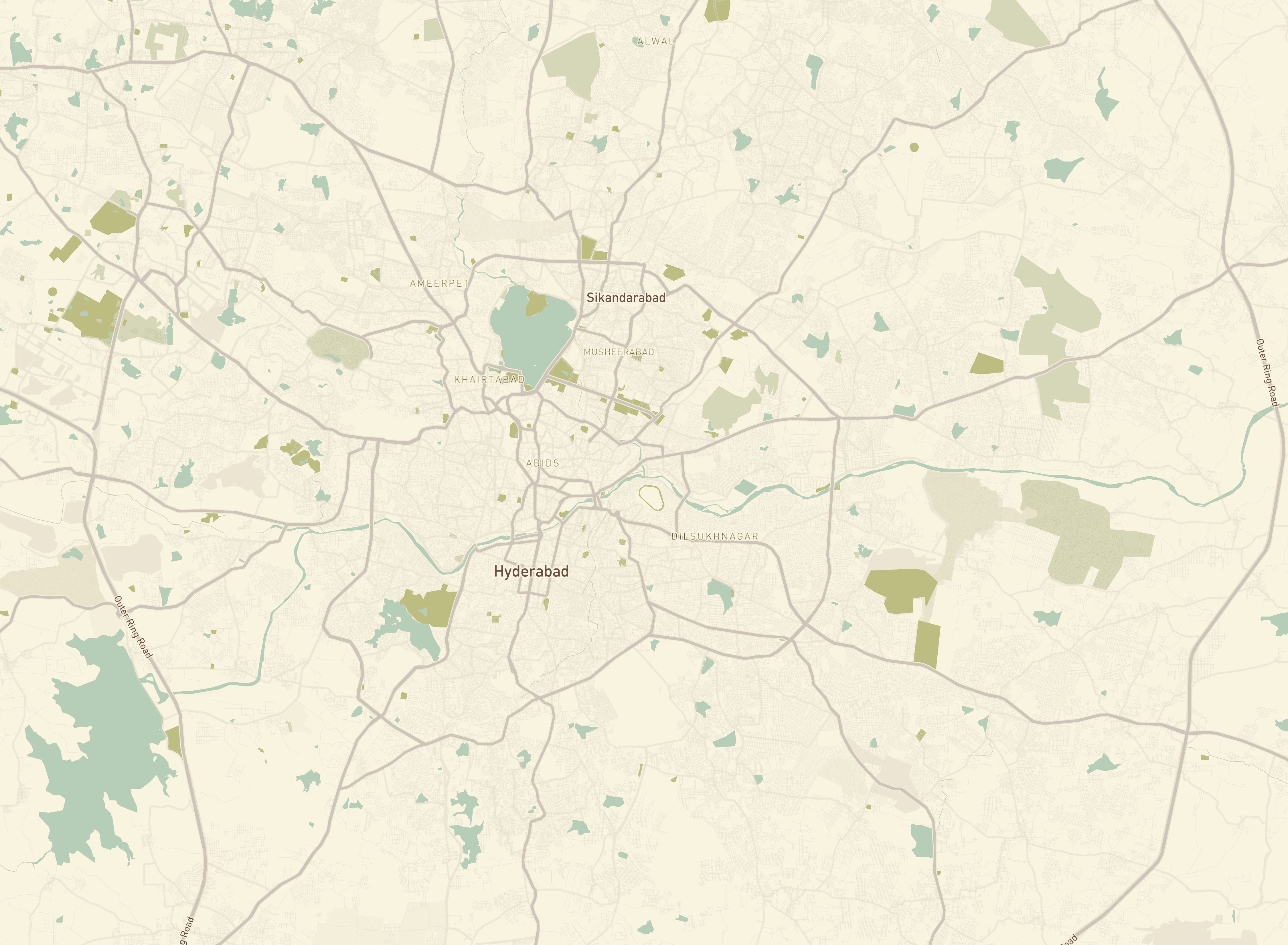

This was a project to create print-ready maps of the cinema halls that existed in Hyderabad from 1936 to 2018.

A practical guide to setting up IIIF image hosting for small archives using self-hostable tools, making collections pannable, zoomable, and annotable without …