How to simply set up IIIF images for your small archive

A piece about my sisyphisean struggle with IIIF while it was still nascent, but in the process learning about new ways of organising for IIIF that favour the smaller archives

For the last few years, I have been in search of a way to host images, text and other types of content on the internet in a no-code or low-code but organized and categorized setup. This has led me to many interesting places and ways of doing this. In this article, I want to talk about hosting images using self-hostable tools.

To briefly talk about why I set about looking for such solutions - I am part of few collectives that work with cultural and creative practice-based research in Karnataka, India. As is, in the course of our work, we come across some interesting collections and collectors of images for different purposes.

A few examples include a researcher studying Memes and Dissent in India looking to have large hoards of images annotated as a community, a 70-year old collector with pictures of a place from a time when very very few pictures exist and a group of dargahs with objects of centuries-old storied traditions. A group of community health workers collecting images and stories of locally available foods, diets and mythologies, multimedia annotations created by performance artists for other artists from a different tradition/discipline.

Each of these examples, require a hosting and publishing solution customizable and annotable metadata and a relatively simple user-management featureset. Back in 2021, I experienced how arbitrary and niche the process of creating a panable, zoomable and annotable image was.

At that time, I was using OpenSeadragon+Annotorious as a way to create the map in this Compost.mag piece. It felt like magic to be able to path that together with whatever little code I knew, like I had cracked it.

“This could be used EVERYWHERE!”

But I found out soon enough - not really!

It felt like every new image I wanted to use this in way would need its own unique pipeline and dedicated resources.

This felt wrong, that something like this wasn’t a native web standard like html. If we are able to annotate text this easily why are images so much harder.

It seemed to be something that could only easily be made in walled-garden platforms.

While working through this problem in 2020, something standing out as having potential was this framework called IIIF (triple-eye-eff) - International Image Interoperability Framework. It was describing a solution that felt a little good to be true.

Yet I saw Archive after Archive listed as examples. I couldn’t believe that these viewing experiences weren’t custom-built monoliths and were based on a standard implementation that I could use if I tried.

I started reading up about it and coming back to it every two months. For a non-technical person like me, it was quite a dense topic to understand. So I tried to learn it by saturation and osmosis.

It was during that time that I started experimenting with Cantaloupe, a IIIF image server. We self-hosted it on a server that our collective owned. After getting to the point of being able to serve singular images, I came across the biggest issue.

- How do I actually organize, metadatize, annotate and then serve these images?

- Is it possible to create a simple user-hosted IIIF archive

- Some possible Alternatives to Github pages

How do I actually organize, metadatize, annotate and then serve these images?

Grappling with the complexity of IIIF

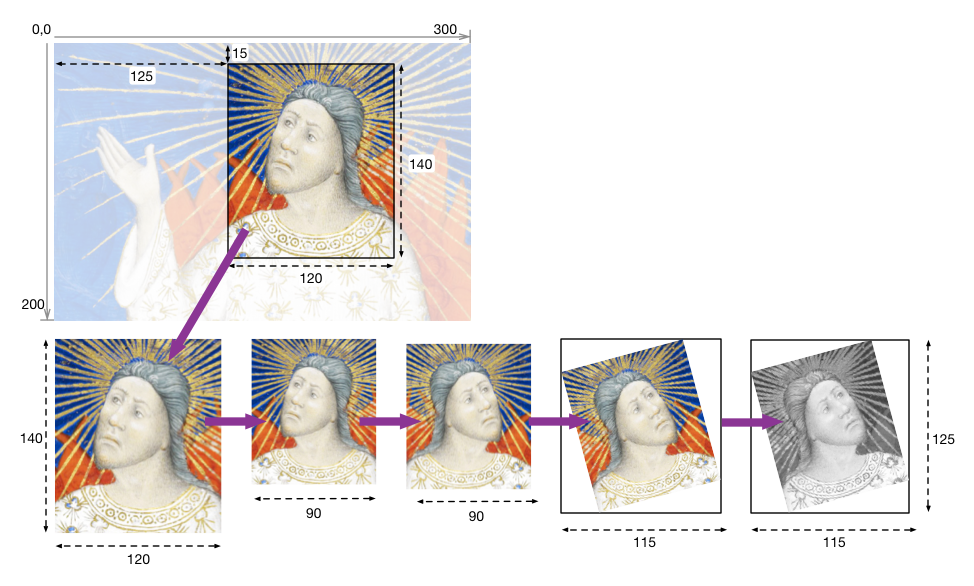

Schematic of how images are requested for and served

Schematic of how images are requested for and served

- This image is a diagram illustrating how the IIIF (International Image Interoperability Framework) works to manage, display, and secure digital images in an online setting.

- The process begins with the IIIF Image Server, where image files and accompanying metadata files (info.json) are stored.

- This server has the capability to transform images (e.g., resizing, rotating, format conversion) based on user needs and is typically accessible over a network.

- The images are then made available through an Image API that enables users to retrieve images in different sizes and formats without needing separate versions of each file.

- This capability allows users to zoom into detailed sections of images, which is especially useful for high-resolution images of artwork or historical documents.

- In another location on the internet, the users create Manifest.json files and stored as bundles that collect images, metadata (e.g., title, description), and structural information (e.g., page order) to organize images or collections for online display.

- These manifest files are passed to a IIIF viewer in a web browser or application, allowing users to view images with embedded metadata.

- The IIIF viewer can utilize additional APIs, such as the Authentication API for access control to restrict certain content and the Search API to enable text searching within images (e.g., searching for keywords in handwritten documents).

- The manifest.json made according to the Presentation API provides display instructions to the viewer to ensure the images and metadata are presented cohesively. This API supports annotations and custom display settings.

As far as my usecases went, this was overkill and far too complicated of a individual or a small archive. So I was looking for opportunities to simplify the stack of things that had to be put together.

As I saw it there 3 main areas where the complexity was really high

The Image Server -

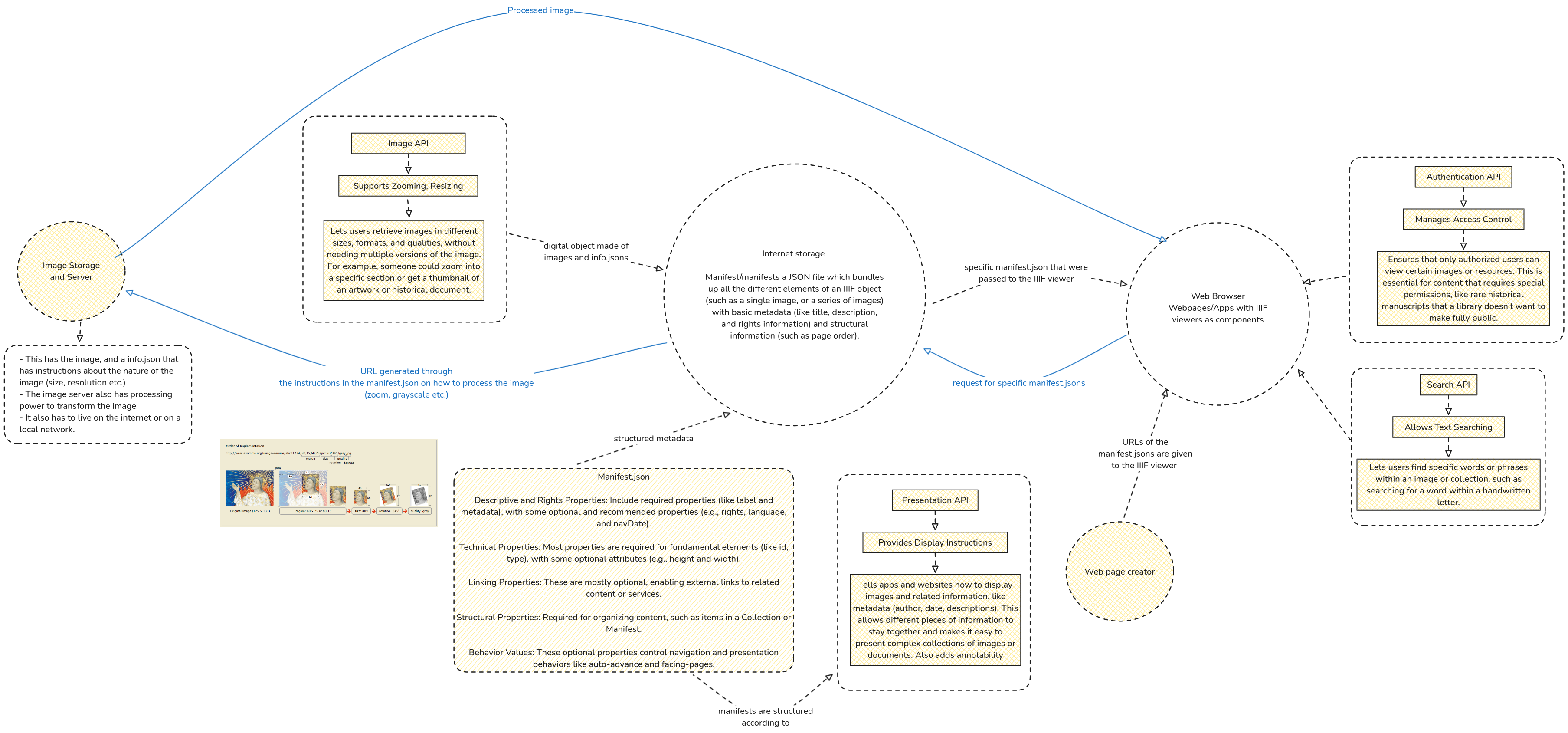

The traditional IIIF image server is a dynamically serving images, cut up into tiles (like maps) - so that they can be viewed at a high resolution. It stores the image, and an accomanying info.json that has instructions about the nature of the image (size, resolution etc.) This has been defined in the Image API.

Dynamic images and how URLs like these fetch them

Dynamic images and how URLs like these fetch them

A simplification that was offered online was to serve static tiles of that don’t do any transformations.

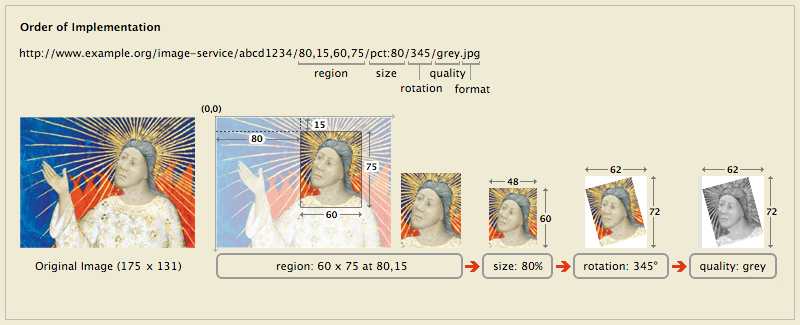

If you think of using Google Maps with a slow network, the squares often take time to load when zooming in or out of the map. Google maps to some extent is dynamically creating these square tiles with upto 22 levels of zoom.

At each Zoom Level, the image is cut up into smaller and smaller tiles - Deep Zoom

At each Zoom Level, the image is cut up into smaller and smaller tiles - Deep Zoom

However, if you were able to limit the viewing to 1 or 2 zoom levels, the tiles can be created once and reused again and again. This is hitting the tradeoff between performance and memory usage.

A github repo with the images pre-cut into tiles at different zoom levels and corresponding tiles and info.jsons could behave like an IIIF image server.

You can see an example of static tiles in this repository of cat pics

This also removes the need for the image URL to be complicated and can be generated according to a formula around the filename.

Manifest Creation:

Manifest/manifests a JSON file which bundles up all the different elements of an IIIF object (such as a single image, or a series of images) with basic metadata (like title, description, and rights information) and structural information (such as page order). According to the Presentation API, here are a few types of properties that a manifest can hold

- Descriptive and Rights Properties: Include required properties (like label and metadata), with some optional and recommended properties (e.g., rights, language, and navDate).

- Technical Properties: Most properties are required for fundamental elements (like id, type), with other property attributes (e.g., height and width).

- Linking Properties: External and internal links - external include logo, see more info, images part of a range etc.

- Structural Properties: items, structures, annotations

- Behavior Values: Asks to define motivation or purpose

As you can see, putting together these things for every image in every collection without the help of a GUI felt very hard, especially because we also wanted the archivists themselves to be able to manage their archives to a large extent.

Here’s an example manifest.json for a small collection

There’s the saying that goes, “There’s understanding and then there’s understanding to teach” - similarly, there’s “building something to use vs building something so that others can build more easily”

The process of putting together Manifests for large quantities of images, is still quite a hard problem. To make matters even more complicated - Manifests are only part of the picture in terms of the structuring required.

Resource Types - Structuring the objects from the image server:

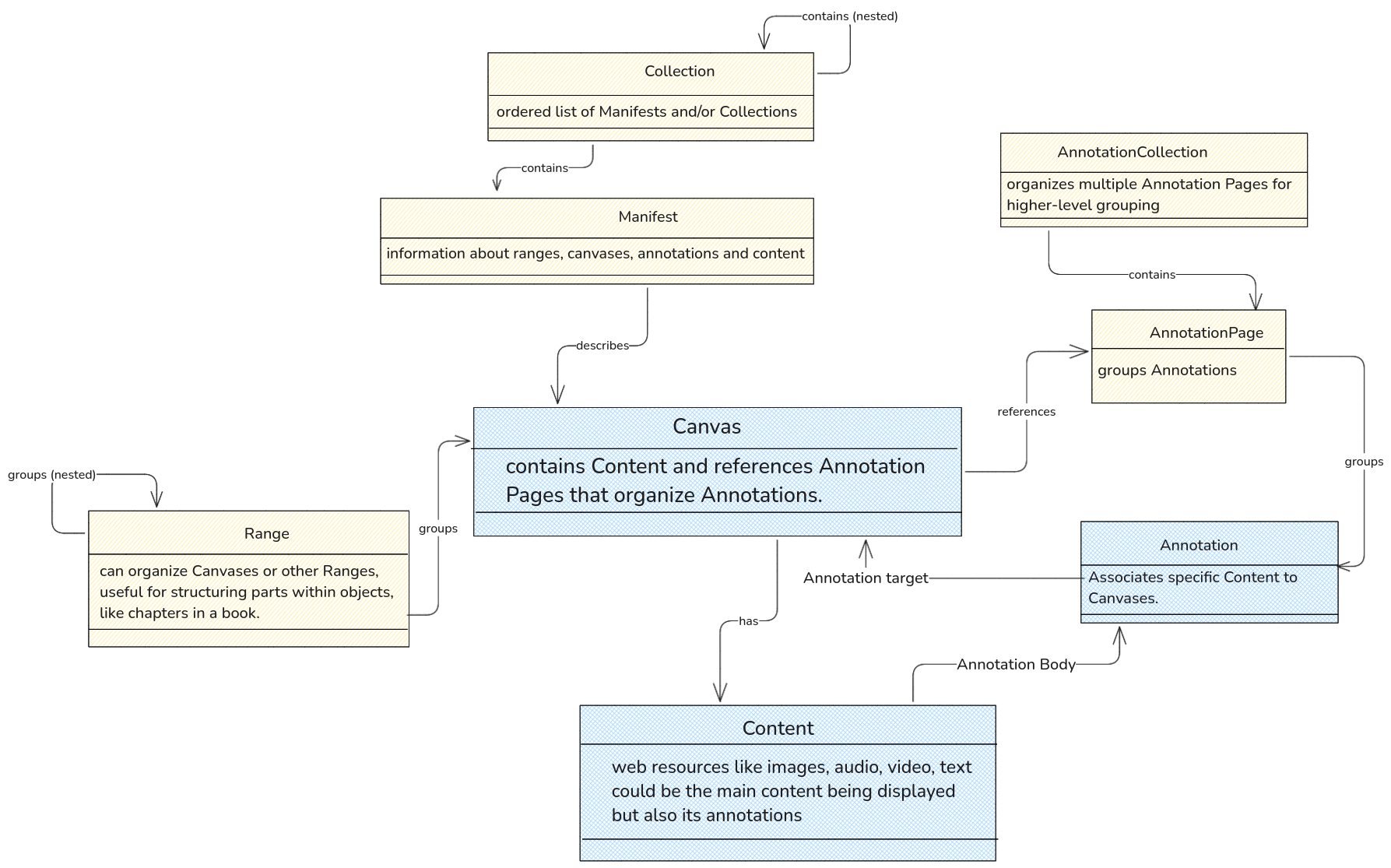

The manifest.json is the part of the object that allows the image to work in a viewer but it is by no means alone. The IIIF Presentation API defines several resource types to structure and present complex multimedia objects. This however means, that it adds to the complexity of the Manifest Creation process.

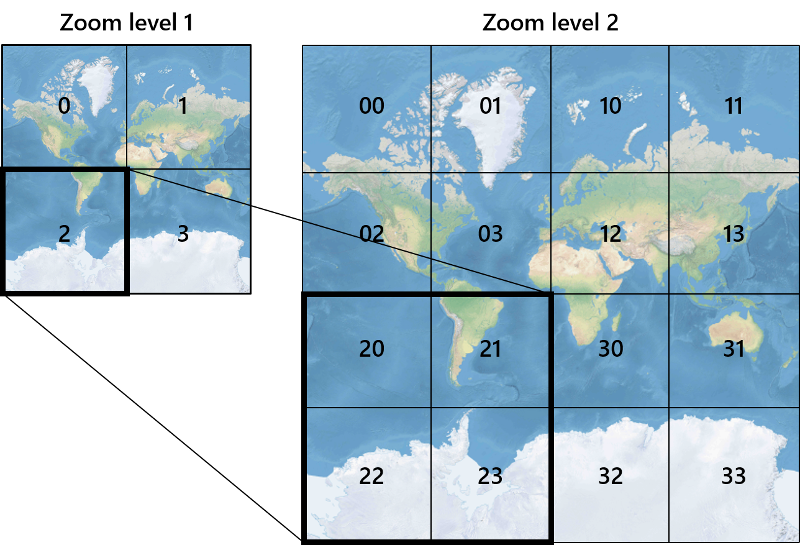

- At the top level is the Collection, which groups multiple Manifests (representing individual compound objects like books or albums) and/or other Collections in a hierarchical way for navigation or organization.

- Each Manifest describes a single compound object, including its metadata and layout instructions for displaying the content.

- Within a Manifest, Canvases represent individual views or “pages” of the object, providing a space for arranging content resources (e.g., images, audio, or video) through Annotations. Ranges allow Canvases or sections of them to be grouped into logical sections, like chapters or scenes.

- Annotations link content resources to Canvases, creating a flexible and distributed system for adding layers of information such as translations or commentary.

- An Annotation Page organizes a list of Annotations on a Canvas, while Annotation Collections group Annotation Pages at a higher level, allowing different types of commentary or translations to be kept separate. Read more here

Creating the Manifests - Organizing the collection

The process of bundling the metadata with the images is also a labour-intensive task. Most institutions that are switching to IIIF for their collections use either custom-built or resource-heavy Content management Software to create manifests. They might also use an Archival Content Management Systems like Islandora, Arches or Omeka. This is however, much harder to do for smaller archivists. For years, there existed no generic way to set up metadata in a spreadsheet(as non-technical people will want to do) and have it converted to a manifest.

Creating Annotations - User-generated metadata

A little less intimidating problem but equally as important is the user-generated metadata or Annotations. How do we enable viewers and end users to create Annotations on these images and have these annotations reflect when viewing them.

Hosting the archive itself

In this configuration, there are a few storage locations that we need to solve.

- Where the images are stored and served from

- Where the annotations are stored and served from

- Where the manifests are stored and served from

- Where is the viewer and archive stored

Is it possible to create a simple user-hosted IIIF archive

A few attempts have been made to simplify the IIIF archive with different opinions on how to simplify this process. A massive simplification is to use github pages

Digirati Manifest Editor

The editor For a smaller dataset, the Manifest Editor is a great tool, if you are willing to organise the images one after another. You are able to annotate and organize the images all in the editor and download the manifest and host it with the images and the html file with the IIIF viewer. Its fairly simple to use, you create or open a manifest, add canvases, add content to these canvases, add annotations and other metadata - preview what it looks like in different IIIF viewers. The viewers that support text-on-image annotations through this method are Theseus and Annona (as of Nov 2024)

BIIIF (Build IIIF)

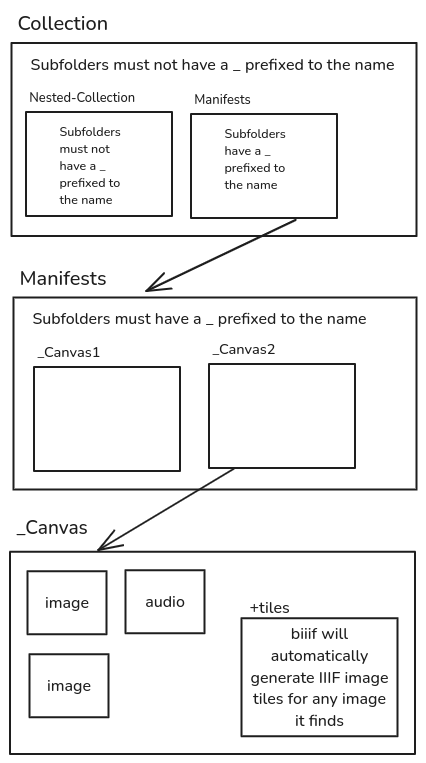

Github Repo This method seeks to use folder hierarchy as a way to quickly organise the collection and generate the manifests. The way it does this is to use a naming convention as a symbol of the various resource types defined in the Presentation API

How the different types of resources in the Presentation API are structured

How the different types of resources in the Presentation API are structured

How to name the folder hierarchy for BIIIF create manifests

You can read more in detail here

After organising the files and folders, the script should create manifests as ‘index.json’ in each “manifest” folder.

To view these manifests, we need to have it on the internet with a URL. This is possible to do with github pages. However, storing the images on a github repository and the manifest, with an html file in which you pass the url of the manifest to the IIIF viewer embedded in the webpage.

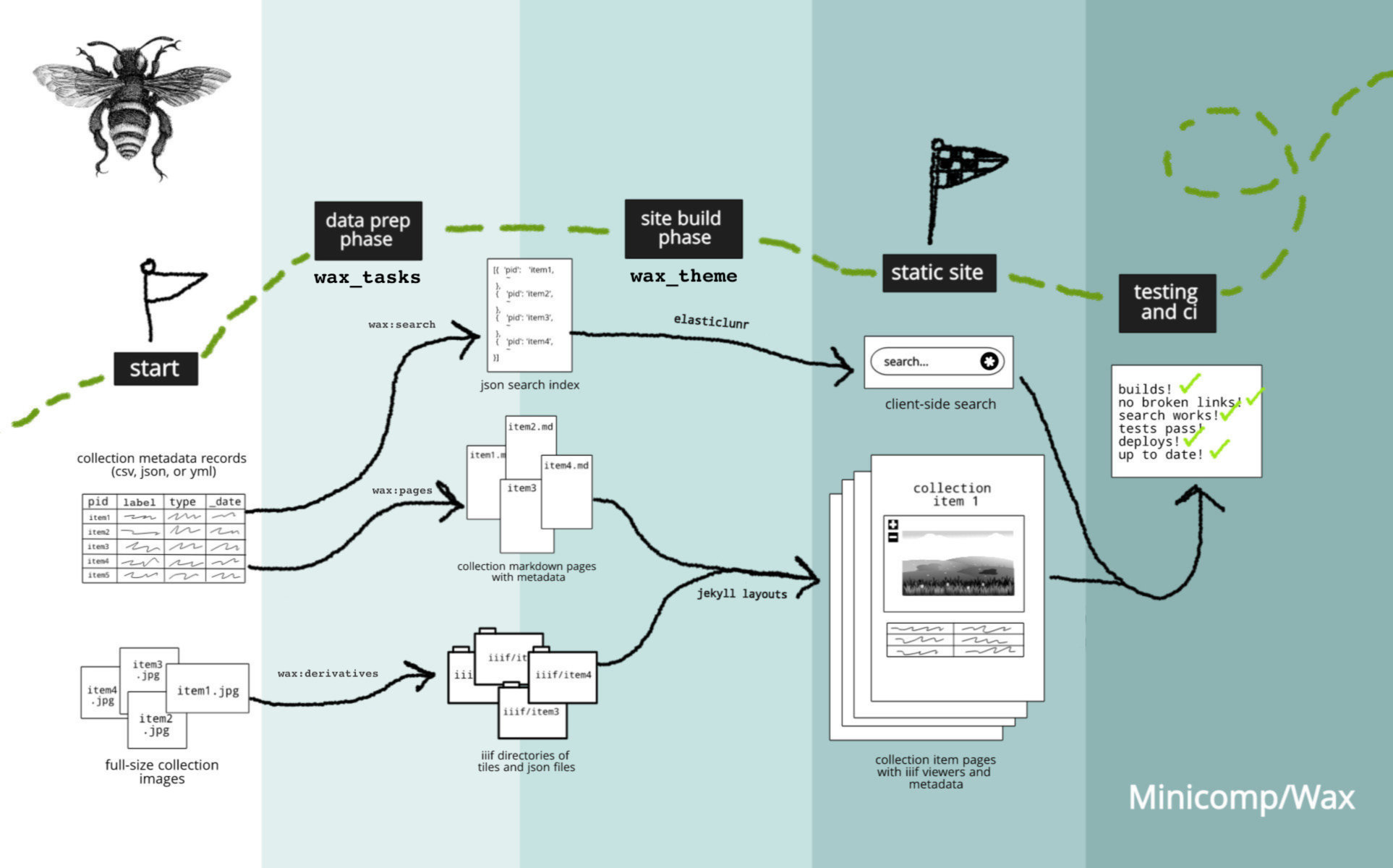

Wax

Wax is an end-to-end workflow for creating exhibitions while following minimal computing principles. It uses a jekyll site with a interesting uses of the ruby plugins like Rake and ready-made jekyll components to create an image exhibition. With github pages, wax is quite extensive and powerful. While tropy would be good for people interested in having a better backend organizing experience, Wax places itself in the better viewing part of the spectrum. It uses the build process to create static tiles, search data as well as creating manifests. The documentation is beautiful and well-thought out as well and is meant for complete beginners to peruse. This doesn’t have any easy method for creating annotations however.

How Wax handles the files and metadata

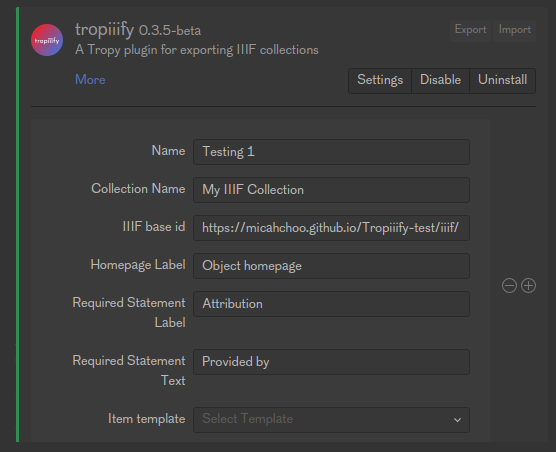

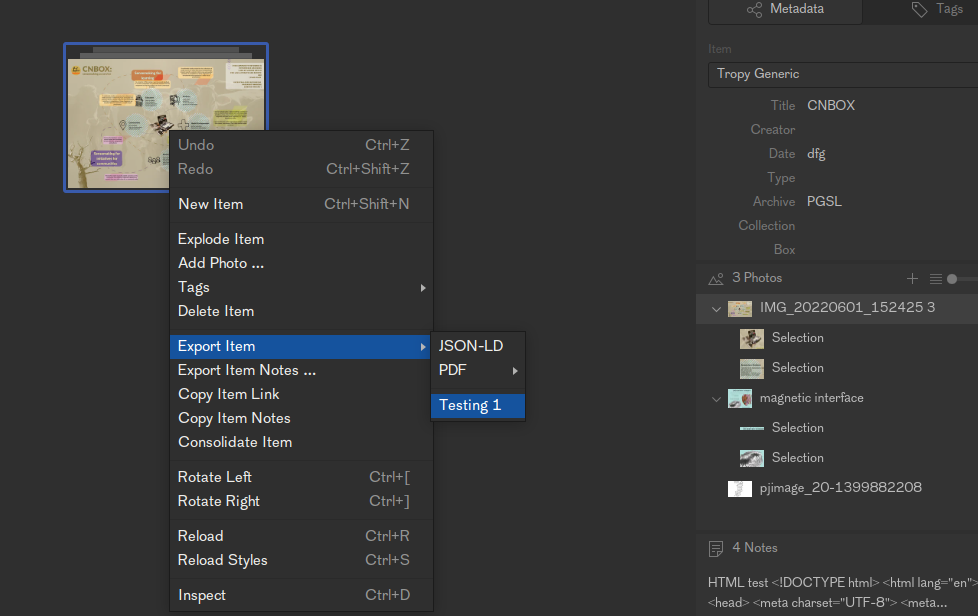

Tropy and Tropiiify

This option seems to be the most promising in terms of the performance and flexibility. When combined with github CI/CD, it can be a complete solution on its own. It is able to provide features that allow organising the files, adding metadata, adding annotation and creating manifests.

While the developers of Tropy have repeatedly asserted that tropy’s data model is good enough for non-image sources, they don’t have time to build support for audio-visual items as well. Being a great organisational suite, Tropy would be well-suited as a multiplayer app. However, as of Sept 4, Tropy dev’s main recommendation is to use a shared folder and be carefull to avoid desynced editing. Collaborative project? - Question - forums.tropy.org

There are a few steps to follow

- Install Tropy

- Download the tropiiify plugin as .zip

- Install the plugin to tropy in the Preferences menu

- Create a repo and activate github pages for it

- In the plugin settings change the base ID to the github pages url till 1 level above the index.json

- Import items to Tropy, organize the images add annotations

- For every item, add a unique number in the identifier field

- Export>tropiiify

- Upload this folder to the github repo you created

- Go to Digirati Manifest editor>Open manifest url>Paste the URL of the manifest.json file from your github pages site

- Preview/Edit or download the json (If changed reupload to Github)

- Create an html page with one of the viewers embedded and pass it the url of the manifest.json

See my test demo here

Some possible Alternatives to Github pages

Gitlab CI/CD

- Someone smarter than me could probably implement it for Gitlab CI/CD. Which could be an exciting possibility.